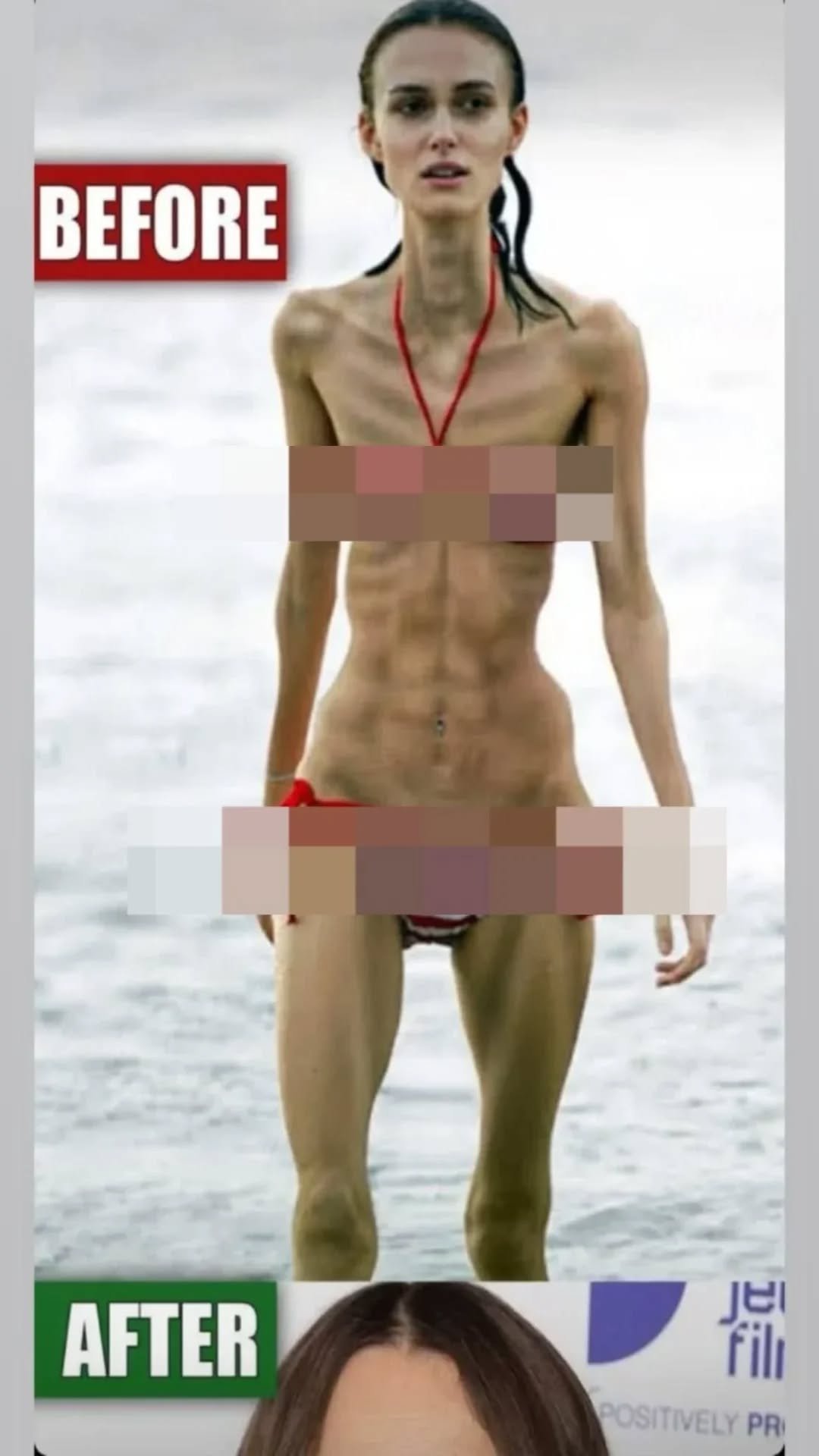

At first glance, the image appears simple: a woman walking out of the water, the horizon blurred behind her, the ocean calm but expansive. She is wearing a red-and-white striped bikini, her posture upright, her expression focused and distant. Yet the photograph does not exist alone. It is framed by labels that suggest a timeline—before and after—inviting the viewer to compare, judge, and draw conclusions that go far beyond the frame.

This is not just a picture. It is a narrative device. It is an example of how modern media compresses entire life chapters into a single visual contrast, encouraging audiences to believe they are witnessing transformation, explanation, or revelation in a glance.

The power of this image lies not in what it explicitly shows, but in what it implies.

A Body as a Headline

In the “before” portion of the image, the woman’s body becomes the focal point. The lighting emphasizes sharp lines, visible structure, and angles that the human eye instinctively notices. The sea behind her fades into a pale backdrop, ensuring there are no distractions. Her frame is lean, her limbs long, her shoulders narrow. Nothing in the photo suggests movement beyond a single step forward, yet the image feels active, as if she is emerging not just from water, but from a moment frozen in time.

This kind of photograph often circulates without context. There is no caption explaining where it was taken, what the circumstances were, or what came before or after that moment. Instead, the body itself becomes the story. Viewers are left to project their own interpretations, influenced by cultural expectations, social media trends, and decades of visual conditioning.

What is often overlooked is that a photograph captures seconds, not realities.

The Illusion of a “Before”

The word before carries weight. It suggests that what we are seeing is incomplete, temporary, or in need of change. It quietly promises that something else is coming—something improved, resolved, or more acceptable by prevailing standards.

But “before” is a construct. It assumes a starting point without acknowledging the journey that led there. The woman in the image did not simply appear in that moment. She lived days, months, and years prior to the photograph—experiences that cannot be measured by appearance alone.

Yet the label encourages viewers to see her not as a person in a moment, but as a problem awaiting a solution.

When Comparison Becomes the Story

The lower half of the composite image introduces the idea of “after,” even if only partially visible. This is where the comparison becomes explicit. The viewer is no longer observing; they are evaluating.

Comparison is a powerful narrative shortcut. It simplifies complex human experiences into digestible contrasts: then versus now, less versus more, wrong versus right. In doing so, it removes nuance and replaces it with certainty.

But certainty in visual storytelling is often an illusion.

The truth is that bodies change for countless reasons—age, environment, career demands, lifestyle shifts, personal growth, and circumstances that may never be visible to an outside observer. To compress those variables into a single judgment based on appearance is to mistake outcome for identity.

Media Framing and Public Interpretation

Images like this thrive in a digital environment where attention is currency. The sharper the contrast, the more engagement it generates. A dramatic “before and after” invites comments, shares, and speculation. It asks audiences to participate, not by understanding, but by reacting.

What happens next is predictable. Viewers fill the silence left by missing context with assumptions. Some interpret discipline, others see struggle, some project inspiration, while others respond with criticism. Each interpretation says more about the viewer than the subject.

This is how images become mirrors rather than windows.

The Human Cost of Visual Narratives

When a single image is repeatedly shared, it can overshadow the person within it. The woman becomes a symbol rather than an individual. Her body is discussed more than her voice, her expression analyzed more than her intentions.

Over time, this process can flatten identity. Achievements, talents, personality, and lived experience are replaced by a visual shorthand. The image becomes a reference point, detached from the complexity of real life.

This is not unique to one photograph. It is a pattern that repeats across media, particularly when appearance is treated as evidence of a story rather than a fragment of one.

The Silence Between the Frames

One of the most striking aspects of before-and-after imagery is what it excludes. There is no room for ambiguity. No space for setbacks, plateaus, or moments that don’t fit neatly into a narrative arc.

Life, however, is not linear. Change does not occur in clean steps, and growth rarely looks the same from every angle. By presenting transformation as a visual endpoint, these images erase the uncertainty that defines real experience.

The silence between the frames is where the truth usually lives.

Why We Are Drawn to These Images

Human brains are wired to seek patterns and stories. A before-and-after image offers both. It promises clarity in a world full of contradictions. It reassures viewers that change is visible, measurable, and definitive.

But this reassurance comes at a cost. It trains us to value appearance over process, outcome over context. It subtly reinforces the idea that worth can be assessed visually, without conversation or understanding.

That belief doesn’t remain confined to screens—it seeps into how people view themselves and others.

Reframing the Conversation

What if the image were viewed differently?

What if, instead of asking “What changed?” we asked “What moment is this?”

Instead of assuming a narrative of correction, we considered a narrative of circumstance?

Instead of labeling one image as before, we recognized it as a moment, neither incomplete nor inferior?

Reframing does not require denying change. It requires acknowledging complexity.

The Responsibility of the Viewer

Images do not exist in isolation. They are interpreted, shared, and amplified by viewers. Each share adds another layer of meaning, another assumption, another judgment.

With that power comes responsibility.

Pausing before reacting, questioning the narrative being implied, and recognizing the limits of visual information are small acts—but they matter. They push back against the tendency to reduce people to appearances.

Beyond the Frame

The woman in the photograph exists beyond the shoreline, beyond the labels, beyond the cropped comparison. She has a life that continues when the camera is gone. The image captures none of that, and yet it is often treated as if it captures everything.

That is the paradox of visual storytelling: it feels complete while being profoundly incomplete.

Conclusion: Seeing Without Assuming

A photograph can show form, posture, and moment. It cannot show motivation, context, or meaning. When paired with labels like “before” and “after,” it gains narrative force—but not necessarily truth.

To truly see an image like this is to recognize its limits.

It is to understand that transformation is not always visible, that appearance is not explanation, and that a single frame cannot contain a human story.

Sometimes, the most honest response to such an image is not interpretation, but restraint.